TL;DR:

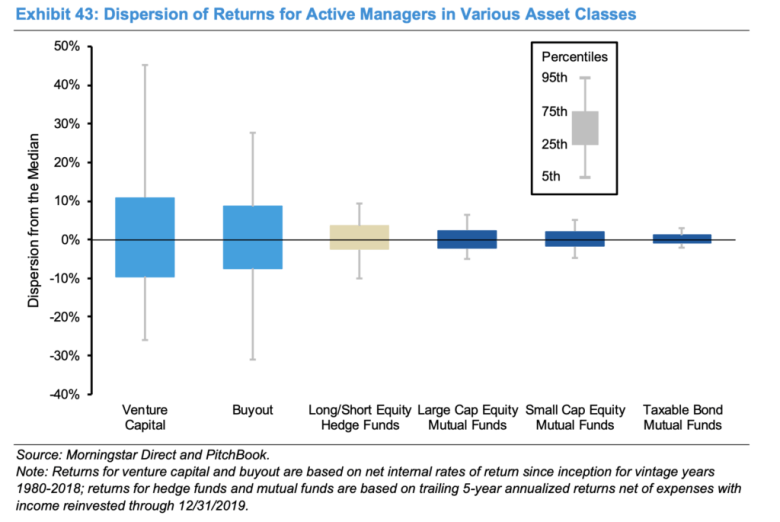

1. Venture Capital generally outperforms every other asset class but the dispersion of returns is wider in venture than anywhere else

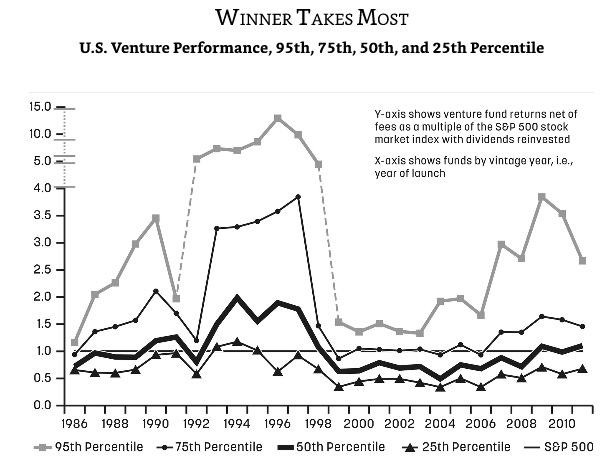

2. Half of all VC funds (supposedly) beat the stock market while bottom quartile funds almost surely lose money

3. The Average VC fund is... average — and top quartile does not quite cut it

4. The performance gab between top quartile, top decile, and top 1% is huge

5. Patience pays off: Let compounding kick in

6. It's a mean world out there!1. Venture Capital generally outperforms every other asset class but the dispersion of returns is wider in venture than anywhere else

There is virtually no other asset class capable of providing returns of more than 80% IRR annualised over a 10+ year fund cycle. Granted, it is the absolute few capable of achieving this (a good return nets out closer to 20% IRR). But while venture has the highest potential upside, the swings and variability can be brutal.

Put differently, the delta between the best performing fund and the worst performing fund - and the best year and worst year - is larger than in any other asset class.

The takeaway: On aggregate, VC is a great asset class with a virtually uncapped upside for the best funds but the variance in performance is high. Vintage diversification and manager selection really matters.2. Half of all VC funds (supposedly) beat the stock market while bottom quartile funds almost surely lose money

A study conducted by NBER with leading economists sampling hundreds of VC funds from 2009 to 2017, suggests that roughly 50% of funds outperforms the public market equivalent (PME), a useful metric to measure private asset classes against.

Widening the dataset and time period, this claim only partly holds true, as recent years have shown a requirement to access the 75th percentile to meaningfully outperform PME:

Other datasets I’ve seen seem somewhat in line but suggest that the breakeven point for VC funds (i.e. returning 1x capital) is around the 50th percentile or median. This is probably a safe assumption to make.

The takeaway: At the median, VC is not really an attractive asset class compared to public index investing. It doesn't materially (if at all) outperform and the illiquid nature and long holding periods makes the opportunity cost high. Investing in a bottom quartile fund will almost surely result in a loss, maybe even already below the median.3. The Average VC fund is, well, average — and top quartile does not quite cut it

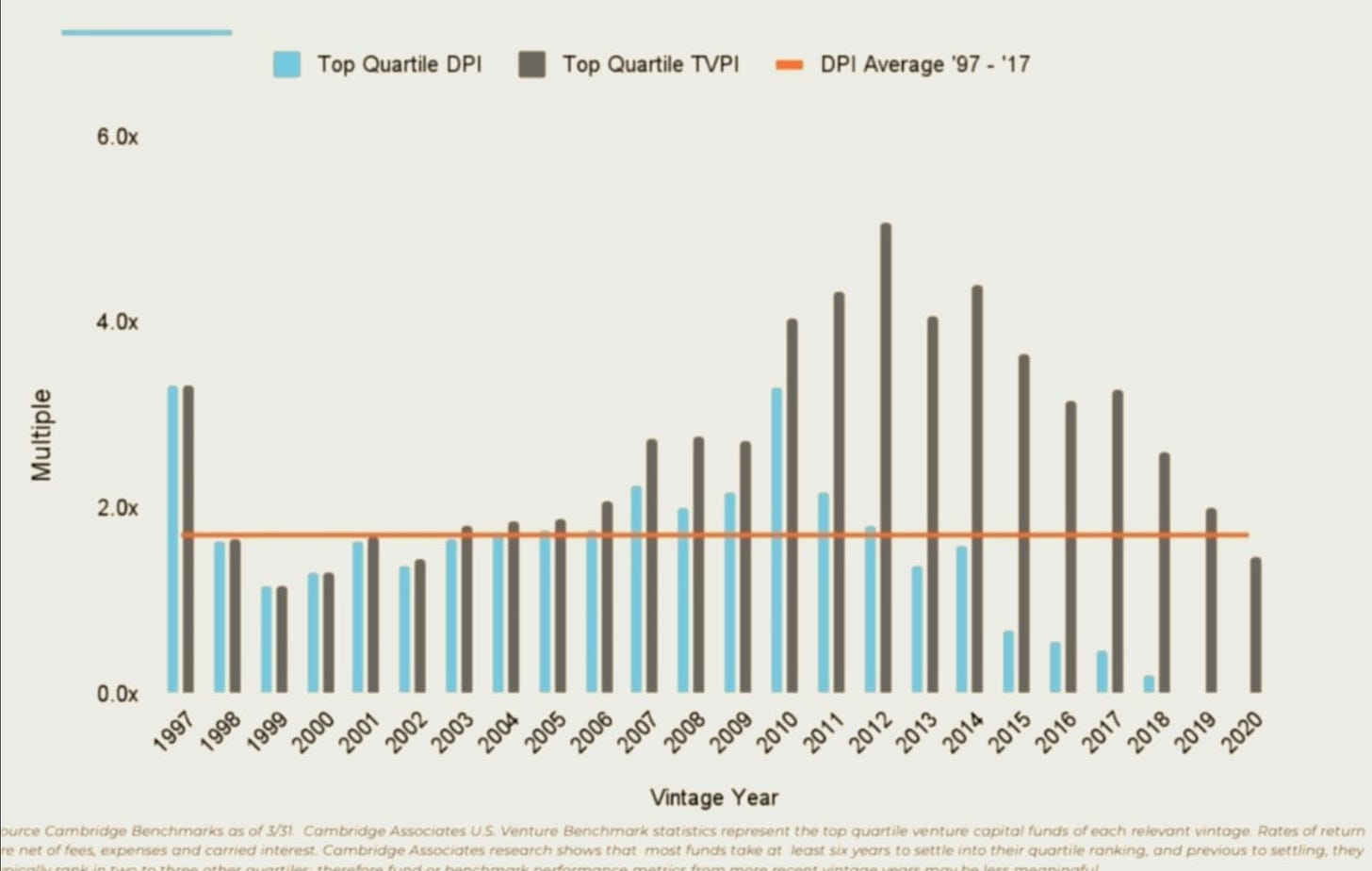

Not only is an average return not good enough for a VC fund, even making it into the top quartile of funds will not quite make you the outperformer LPs are looking for:

The takeaway: LPs in early stage venture funds are underwriting to minimum a 3x return on their capital. To achieve that, you need to be better than top 25% of all funds4. The performance gab between top quartile, top decile and top 1% is huge

So what does it take to achieve outsized returns (above 3x on a fund level) in venture?

David Clark of Vencap shared this recently:

Pitchbook has DPI data on 1,186 VC funds raised from 2000 to 2015 (so at least 8 years old). Of these 1,186 funds, just 181 (15.3%) have DPI of 2x or higher. 70 (5.9%) have returned 3x or more back to LPs and only 25 funds (2.1%) have distributed 5x to investors.

Taking into account that those funds still have some unrealised returns (TVPI), it is reasonable to expect the DPI numbers to improve slightly. According to David Clark’s guesstimate, this would mean ~10% of funds exceeding 3x net performance.

This would be in line with an observation from Meghan Reynolds of Altimeter, stating that only once since 1998 has the threshold for being in the top quartile of funds exceeded 3x. And the threshold to be in the Top 5% has exceeded 3x in only 13 out of 25 years.

Samir Kaji, citing Pitchbook benchmarks, notes that Top Decile Net TVPI multiple is 3.06x while Top Quartile Net TVPI multiple is 2.39x. Applying a TVPI to DPI discount, this nets out closely to the numbers above.

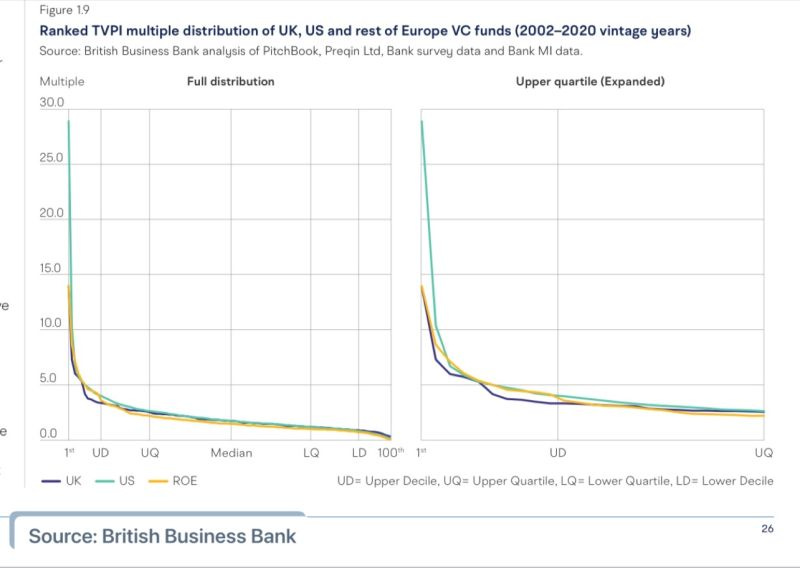

Not only is VC dispersed around the median but zooming in on the top quartile or top decile suggests that the within-quartile-difference in performance is also extreme.

The takeaway: Fund returns are power law distributed, and to exceed LP expectations a fund would need to be in the top decile, not top quartile. Returning 3x net to LPs will likely get you there.5. Patience pays off: Let compounding kick in

Not only do you (and your LPs) have to contend with the downward slope of the J-Curve in the early years of a fund, the real returns will likely not materialise until the out-years of the fund cycle (meaning 10-15 years in).

Beezer Clarkson of Sapphire expect to see a loss ratio of 20-30% and close to zero DPI in the first five years of an early-stage fund. Meaningful cash returns is not expected until year 10. As such, DPI will look dramatically different in year 10 versus year 5.

Even at year 10 it pays to be patient. As Jamie Rhode from Verdis has pointed out: the last years produce the outlier returns. If a VC fund is producing yearly returns of 25% IRR (making it a good fund), over 9.5 years it becomes a 8.5x fund — but over 13 years it grows into a 14.5x fund. Put differently, the last 20% of an early stage fund’s life is responsible for almost 50% of the overall return.

The takeaway: Patience is indeed a virtue, especially in venture. One of the biggest mistakes an investor can make is to let go of an outlier investment too early. If you're right, make sure you end up getting paid for it.6. It’s a mean world out there…

Venture capital is undoubtedly an asset class unlike any other. The returns are potentially unbounded, making it an extremely attractive investment opportunity — if you get it right.

Just as VCs are chasing the outlier startups, LPs are chasing the outlier funds, making it an interesting and important game of selection.

The power law distribution makes a massive difference between extraordinaire, great, and good returns — as evident in the meaningful difference between the industry’s median (10% IRR) and mean (50% IRR) return, a differential driven by the top <1% of funds.

The takeaway: Indexing venture capital as a whole could in theory be a solid investment but it would require capturing the entire industry, as one cannot afford to omit the few outliers driving up the mean.

This nicely illustrates a point by Nassim Taleb that looking at averages and standard deviations is useful in Gaussian worlds but not at all in fat tail worlds with very extreme events (such as venture).Curious to hear any additional views on this topic. Feel free to leave a comment, DM me on X or LinkedIn, or reply to this via email if you’re a subscriber.

Avoid Vegas at all costs

How to Write A Proper Rebuttal https://open.substack.com/pub/michael880/p/how-to-write-a-proper-rebuttal?r=3b6pw1&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web